Those who were once called insane for seeing beyond the obvious are the same ones whom humanity recognizes centuries later as geniuses. What today is ridiculed as delusion, tomorrow is elevated as vision. The mechanism is almost always the same: first you’re insane, then—in some cases—eccentric, later a visionary, and in the end you’re called a genius, almost always after death, when you no longer represent a threat and are not alive to witness it. But this transition is not guaranteed. Most die and remain only as insane, forgotten or erased. Only a few are reclassified by time, when power or History find utility in the myth.

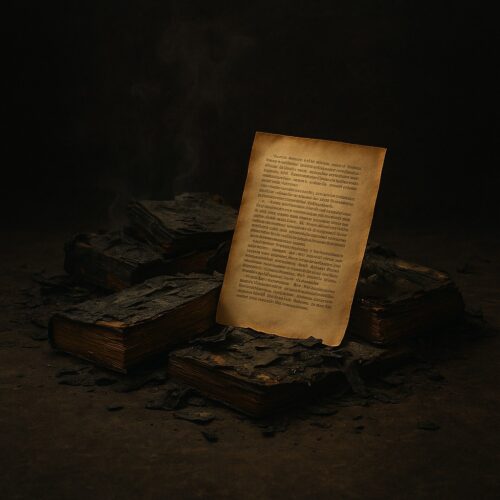

Machiavelli died without glory, seen only as a suspicious and irrelevant functionary. The Prince, ignored in his lifetime, ended up becoming the secret manual of kings, politicians, and all who aspire to power. If the elite had allowed it, that book would never have reached the hands of the public. And we cannot forget that for centuries it was banned and burned in public squares, a book condemned to the flames by the very system that later turned it into a reference manual. If that silencing had been absolute, Robert Greene would never have written The 48 Laws of Power, today one of the most famous works on manipulation and strategy. The Prince was the foundation that opened the way for Greene, who carried those ideas into the 21st century and to the masses.

Beethoven, in the final stage of his life, was seen as a deaf eccentric waving into the void, and today he is untouchable in the pantheon of music. Van Gogh died poor, rejected, unable to sell his work, but centuries later his paintings are treasures. Galileo was condemned and silenced by the Church, and now is celebrated as the father of modern science. Tesla died broke and ridiculed, but he is the basis of much of electrical and wireless technology. Kafka wanted to burn his own manuscripts, because he believed they had no value, and today his work is inescapable. Oscar Wilde was humiliated, imprisoned for homosexuality, but today he is celebrated as a literary genius. Nietzsche died insane and despised, and today is a pillar of modern philosophy. Schopenhauer was ignored in his time, but later considered master of philosophical pessimism. Alan Turing, condemned for homosexuality and dead in disgrace, is now recognized as the father of computing.

The pattern is clear: those who break with the dominant vision are crushed while alive, only to be canonized after death. The system must first eliminate the threat, neutralize the difference, and only then does it grant the label of genius. Recognition is almost never given in life. It only happens if the elite want to use you as a tool while you’re still breathing. Otherwise, they wait for your death to recycle you into a myth, when you can no longer resist or speak for yourself.

And here is the key: the label of genius is not born from justice, it is born from convenience. Power decides when an insane person serves as an example and when he must remain buried in oblivion. Global elites and cultural markets choose who gets recycled and who gets erased. The waiting time—sometimes centuries—is intentional: only when the threat disappears is it safe to turn the rejected into an icon.

The posthumous genius does not serve the creator, it serves the system. The work and the figure are appropriated to legitimize regimes, inflate markets, strengthen official narratives, and provide secret manuals of power. Yesterday’s insane is only celebrated when he can no longer speak for himself and when his image becomes useful as a tool of domination.

This is where the engineering of collective memory comes in. It’s not truth that decides who is remembered, but usefulness. Talent creates the work, but it’s the elites who decide whether that work enters History or gets erased. Memory is selective: some are manufactured as eternal symbols, others are buried as if they never existed.

Talent can create, but only the elite decides who deserves to be called a genius.

September 2025

This article is in English. Read the Portuguese version ⇒ Ler em português